The Insperable History of Math and Gambling

9 years ago

16 Jun

The use of mathematics by gamblers is obvious and pervasive. Concepts like Expected Value, Bayesian Probability, Kelly Criterion, and Nash Equilibrium are all part and parcel of the business of risk. Some ideas of mathematics are even used intuitively, without knowing the origins or names.

But this is a two way street, and it has often been in trying to turn a profit at the card table that the study of mathematics has been advanced. The most obvious point of intertwinement comes in the field of probability. There would be little point in listing every concept from mathematics which gambling has helped along, but we can follow this thread by way of an example.

The Problem of Points

The most famous of these intersections comes in the exchange of views between Pierre de Fermat (of Last Theorem fame), Blaise Pascal (he of the god wager), and Gerolamo Cardano (who knows). They were debating, via letter, something known as the Problem of Points.

The Problem of Points is essentially a debate about how to fairly divide the stake in a game of chance which has been interrupted. A rough comparison might be how to negotiate a fair chop on a tournament final table.

The problem had been originally proposed in the late 1400s where the solution provided was simply to split the stake on the basis of how many rounds each person had won with no regard for how the future rounds might play out.

This solution didn’t hold much water. To see why, think about what happens when only one round has been played. How fair is it to award the whole stake to one player over the other in a first to 1,000 coin flipping match? Or, to look at it a similar way, if you were 43 flips into those 1000, and then you were interrupted, splitting evenly would seem unfair. Even though the payout was designed for 1000 flips and whoever was ahead had not yet won, they were still ahead.

Expected Value

Further refinements had been offered before Pascal and Co came to the problem. For example factoring the size of the lead in each round.

Pascal wanted something more generalisable, more abstract. Starting from the fact that the odds of winning are the same with a score of nine to five race to ten, or a score of ninety-nine to ninety-five in a race to one-hundred.

Pascal approached the problem as one of combinations. How many situations can occur? And how many result in a win for each player.

In the case of the nine to five (or ninety-nine to ninety-five lead there are six possible strings of outcomes. The guy with nine wins all but the outcome where the player with five wins the next five rounds in a row. Any other sequence ends when the guy with nine wins a round. So the odds are ⅙ for the guy with five. So he takes ⅙ of the pot. Fair’s fair.

From this, Pascal generalised the idea, now accounting for varied bet sizes and differing probabilities of winning for each player per round, into the concept of Expected Value or EV. A term which has entered the common argot of poker, especially online.

An Explanation for Everyone Else

For newcomers, Expected Value is – without being terribly rigorous – the long term average outcome of a given gamble. Slightly more rigorously it is the sum of all possible outcomes multiplied by their likelihood.

The easiest example is the case of a fair coin. If I bet you my £2.00 against your £1.00 at that it comes up heads then the possible outcomes are that 50% of the time you make a profit of £2.00, and 50% of the time you lose £1.00. The maths looks a little like:

- EV = (£2.00 x 50%) + (-£1.00 x 50%)

- EV = £1.00 - £0.50

- EV = +£0.50

So on each throw, you expect to win an average of 50 pence profit and should play the game for as many rounds as my accountant will allow me.

...and we’re back

The implications for the Problem of Points was simply that if you knew the likelihood of winning a given game, you could feed that into the formula and it would spit out the amounts each player deserved.

Christian Huygens, in a treatise you can read in full online, took the principal further and ironed out Pascal’s work on expected value. With a basic tool for assessing probabilities in this way, an entire field of mathematics grew out of it, expanding on his work and integrating it into the greater edifice of mathematics.

Huygens work was then picked up by Montmort in his Analysis of Games of Chance where he continued to develop mathematical ideas from the problems raised by trying to win at cards. From these pages, a practical gambler’s problem rears its head and – just like the Problem of Points – lays the groundwork for another field of mathematics.

A New Game (Theory) in Town

The problem in question is now known as the Waldegrave Problem after Charles Waldegrave, who picked up on a question relating to the best strategy for a simple card game called Le Her.

His solution to the problem is, in modern parlance, known as a minimax mixed-strategy. This means it is strategy which minimises the risk of the maximum loss (minimax) an end that is achieved by playing more than one strategy at given frequencies (mixed-strategy), from round to round.

In the approach to this problem, are the seeds of Game Theory, the mathematical (or economical, depending on who you are arguing with) field which is used in fields as diverse as taxation, evolutionary theory, and the Mutually Assured Destruction school of nuclear deterrence.

It is also an important tool in poker, where opponents not only have numerous strategies available to them, are playing with a range of possible hands, and are trying to account for the strategies of their opponents.

Game Theory as a field remained dormant after this initial foray until the appearance on the scene of John von Neumann, a disgustingly talented polymath who made all sorts of useful advances in maths, physics, biology, and, for our purposes, the in invention of Game Theory.

Von Neumann laid out the beginnings of the field in which A Beautiful Mind’s John Nash won his Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel (all together now: ‘there is no actual Nobel Prize for Economics’).

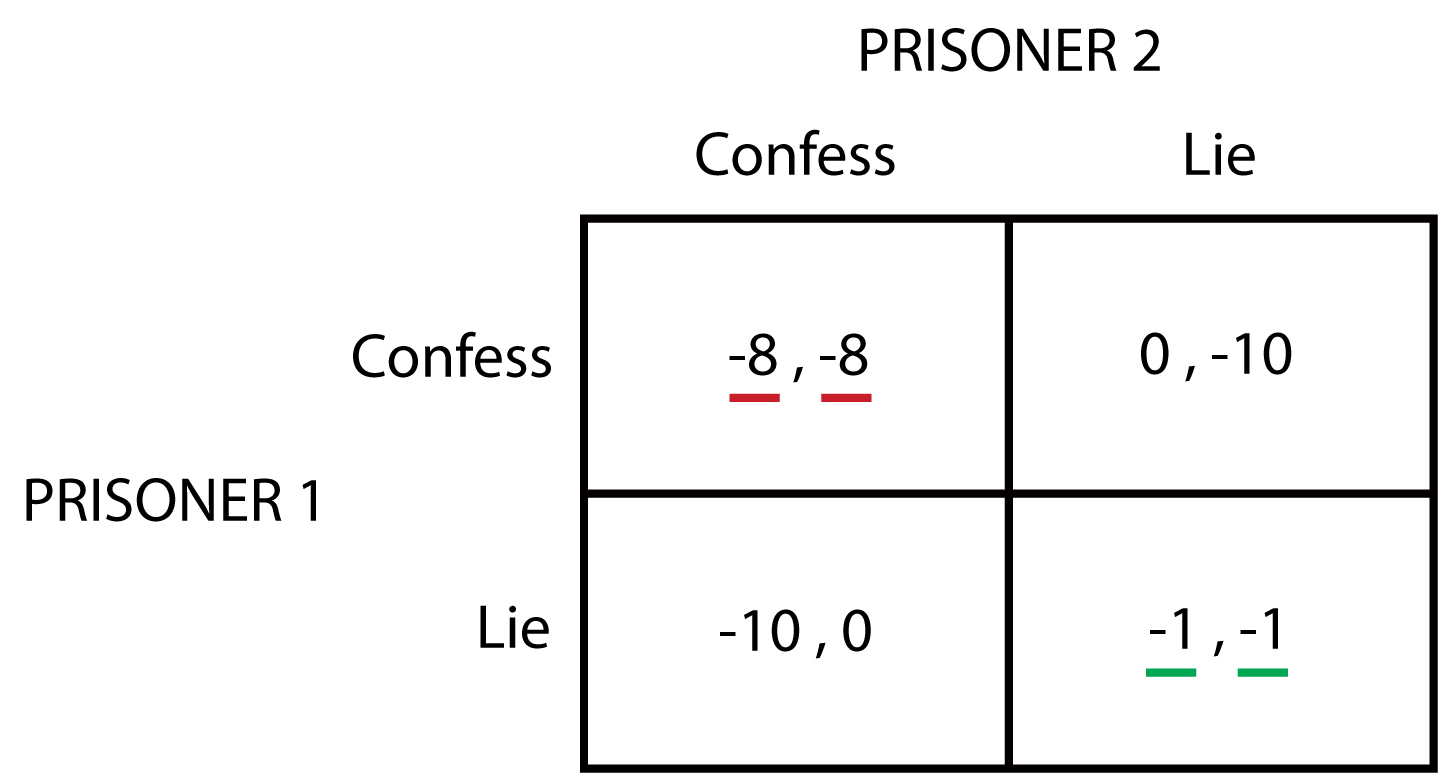

Discussions of game theory usually start with The Prisoner’s Dilemma:

The Prisoner’s Dilemma

This is the classic introduction to game theory and it gives a flavour of how Game Theory looks at strategy. The basic method can be, and is often is, applied to much more complicated problems, like the kind you see at the poker table.

The situation is this. Two prisoners are held in separate cells and are offered the following dea

You can either squeal on the other prisoner or keep schtum. If you both say nothing you both do one year. If only one of you speaks they go free, the other goes to jail for six years. If you both speak, you both do two years.

The tool used to analyse this sort of thing is a Payoff Matrix which looks like this:

Player 1 (Tattles) | Player 1 (Keeps his mouth shut) | |

Player 2 (Tattles) | Player 1: 2.0 Years Player 2: 2.0 Years | Player 1: 6.0 Years Player 2: 0.0 Years |

Player 2 (Keeps his mouth shut) | Player 1: 0.0 Years Player 2: 6.0 Years | Player 1: 1.0 Years Player 2: 1.0 Years |

Player 1 knows that whatever Player 2 does, their best option is to talk. Player 2 knows Player 1 knows this, and Player 1 knows that 2 knows they know, so, it is pretty obvious that boths player’s best move is to sing like a canary and take their two years.

Problems like this, of ever increasing complexity, give absolute solutions to all sorts of poker spots, given certain assumptions about your opponents hands and their ability to play close to the strategy dictated by game theory.

And So On

This particular thread through probability and game theory is one of the strongest examples of gamesters and mathematicians passing information, questions, and answers back and forth, but there are plenty of others.

The Monte Carlo method grew out of a question about solitaire and is now a sort of mathematical tool for running numerous randomised trials of an event, allowing a gambler or mathematician to avoid having to figure out combinatorial solutions for hugely complex systems. Chaoticians look at unpredictable systems, abstract as well as real, a field of great interest to the big-budget gamblers of Wall Street who need tools for dealing with the random walk of the markets. Bayesian mathematics is used by epidemiologists and other academics, as often as it is to set the prices at your local bookies.

Gaming has clearly taken the bulk of its serious thinking from the world of mathematics, but it frequently ends up with something to give back. In some cases it’s hard to tell where the maths stops and the degeneracy begins.

Comments

You need to be logged in to post a new comment